By Kanika Bhatia

Few years ago I ran a blog that featured a story on invisibility. I had traveled to Mcleodganj, visited the quintessential spots, and spent an hour with some local children. The story spoke about their simple desire to talk. That’s it. Just like that 60 minute conversation, their desire was fairly simple. Do you see us? Please do.

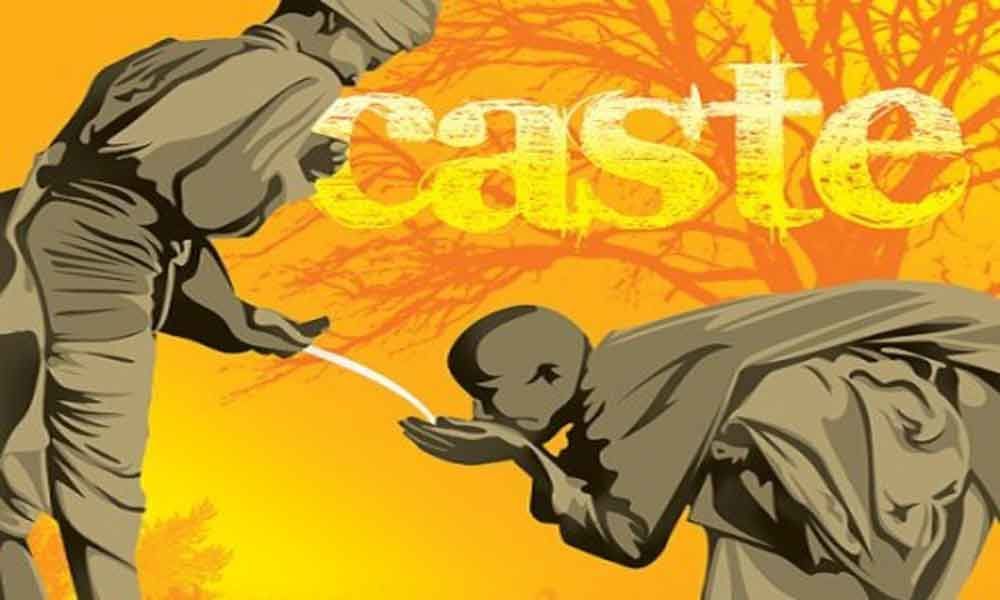

Years later, I woke up to a systematic banishment of generations of groups. When you raise this theme in sophisticated circles, it usually ends up disregarded with one statement: “It doesn’t exist anymore.” How do we then explain Dalit targeted rapes, menial jobs still limited to certain sections, ghettos, sewage cleaning “accidents”, garbage segregation jobs, and the large question of identity that still looms over the head of 75% (probably higher) population of this country. You choose not to see it, but it exists. Rampant, aggressive and ubiquitous.

The patriarch of my family followed Arya Samaj. It wasn’t until last month that I fully grasped what it meant, because to a young eye, we did hawans and that’s it. I wasn’t ever a fan of his methods or him if am being honest, but to the sparing attention of a teenager, religion/ culture/ social capital is the last concern. How problematic Arya Samaj is in its conception, how it dictates so many of its loyalists to further a cause that saw relevance some centuries ago, and is nothing short of horror to my “modern” understanding is something I am only beginning to gnaw at. THIS absolute disregard for what happened in my own courtyard is another format of this naked invisibilisation.

“I don’t see caste” “I don’t question someone’s identity” “My decisions never revolve around caste” : the war cry of modern liberals like myself. The logic being simple, haven’t done bad, but haven’t done good either. The idea that we don’t see caste, despite the very visible format in which it exists, is a privilege. A famous anecdote goes where a child asks his mother, “mother, what is my caste?” The mother tactfully replies, “If you don’t know it yet, you’re probably an upper caste.” Most oppressed groups share a common theme, they are aware of it. Infact, they are reminded of it with that extra layer of awareness no matter where they are or what they do. I am a woman, more so because no one lets me forget it even for a second. You’re stepping in an elevator or you’re walking down for groceries, you are vigilant. Subconsciously I know eyes that are digging through my clothes. If I am careless, there will be someone who will ensure I don’t falter. The privilege of the upper caste exists when you’re not reminded of it every waking hour. Dismissing its existence is a disservice of blinding yourself and those around you to a very real identity crisis still enveloping as India moves to celebrate its 75th year of independence.

A young blogger, Tejaswani Tabhane pointed out, “Blindness to caste does not take the social, political and economic privileges one gets because of one’s “accident of birth” in a particular (upper) caste. To be born in a privileged caste is not anyone’s fault, but to refuse to even acknowledge “unearned benefits” accruing due to one’s caste and thereby claiming that the very mechanism that enforces them is absent in one’s life isn’t right.” The countless spaces where I haven’t seen caste before haunt me now. Why didn’t all your reading, awareness allow your senses to observe that nearly every menial job around you is being done by someone who doesn’t belong to an upper caste? Who segregates your garbage when you mindlessly give it to the ‘koodewale bhaiya.’ Why is this systematic denial of growth not being discussed in the elite circles? Unseen, not just sidelined.

I learnt about TM Krishna and his new book recently: Sebastian and Sons. If you don’t know him, he is a renowned Carnatic singer and activist who is very vocal on casteist biases in his field and beyond. The book talks about mridangam makers, making and its players. Considered the “king of percussion,” Mridangam is a paradox within itself. Played by brahmanical and elite players, it’s made from the best cow hides the maker can find, only to be used in reverence of Nandi, Shiva’s bull. The invisibility that we spoke of above? This practise sounds like the perfect example of brahminical worlds hypocrisy masked by its blindness. The profound and profane coexist.

I am far from being an expert or an ally on the subject. However, like the accidental hail with rain, came the epiphany. You can read Ambedkar, Phule all you want, but till you don’t SEE them (IT), it’s meaningless to even begin the conversation. Information is our generation’s blessing; you can learn everything from caste to cakes. Whether it’s an academician, activist or a humanitarian lens you wish to use, use it. Don’t pretend you can’t see it. It is screaming for your attention.