Ashmi Sheth

Book Review, International, Arts & Culture, Literature

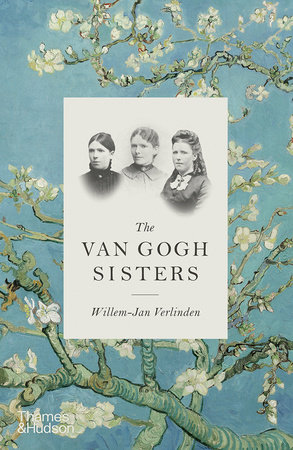

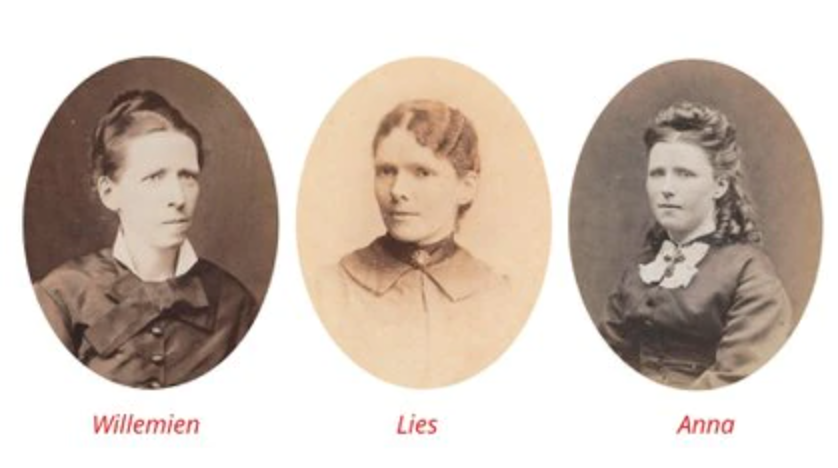

There would hardly be an art lover across the world who hasn’t heard of the celebrated Dutch painter, Vincent van Gogh. At the same time, not many are aware that Vincent had three younger sisters: Anna (eldest), Elisabeth (Lies) and Willemien (Wil, youngest), who had a great influence on Vincent’s life and career turns. Willem-Jan Verlinden, in his book, The Van Gogh Sisters, makes an attempt to throw light on the Van Gogh sisters and other women who influenced Vincent’s life, career and escalating fame. The book, based on the letters exchanged between the sisters, Vincent, Theo and their parents, paints a vivid picture of the varied lives of Van Gogh sisters, their complex relationship with Vincent and the other family dynamics that were in play throughout the four generations of Van Gogh.

The book starts with the marriage of Reverend Theodorus (Dorus) van Gogh and Anna Carbentus-van Gogh, parents of Vincent and his five siblings. It then delves into the childhood of Van Gogh children, traveling through their adolescence, shift in roles and residencies, marriage and post-married life. The tragic event of Vincent’s death is described and its influence on the lives of the Van Goghs is elucidated. The book continues well through the death of all the Van Gogh siblings, elaborating on the lives of all three sisters who lived into old age, contrary to their three brothers who died young.

Verlinden’s book clearly describes the differences in the lives of the three Van Gogh sisters based on their birth order and the changing opportunities for women during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Wil, the youngest sister had a life vastly different from that of her elder sisters, Anna and Lies. “She never married or had any children, and pursued independence.” Verlinden writes that social work – education, caring and nursing – was the only sector in the Netherlands in the second half of nineteenth century that offered paid work to women from the upper middle class, to which the Van Gogh family belonged, and Wil exploited this opportunity to the fullest. As early as in 1893, Wil qualified as a scripture teacher and took up a position as a substitute Bible teacher in a city to east Netherlands in the same year. Wil would also go on to become one of the most active participants in the first wave of Dutch feminism in the late nineteenth century. Along with her close friend Margaretha Meijboom, and her neighbour in Prins Hendrikstraat, Margaretha Gallé, Wil joined the organization committee of the National Exhibition of Women’s Labour in 1898, which aimed to readjust the image of women’s ability to contribute to the labour market. Verlinden explains how this was an opportunity for these progressively minded women to put their ideals – advocating for increased accessibility to education, effective social work, and a reform of the role of religion in everyday life – into practice. He notes that coming from a traditional Dutch Reformed household, joining one of the first feminist associations of the Netherlands was not a natural decision for Wil; yet she “took to the cause enthusiastically and with dedication.” Unfortunately, Wil couldn’t continue her struggle for women’s rights in the Netherlands due to the decline in her mental condition. She spent over thirty years, about half of her later life, in the Veldwijk psychiatric hospital in Ermelo, where she would die in 1941 at the age of 79.

Vincent was closest to Wil, with whom he shared a love of religion, art and literature, and they often openly discussed their struggles with mental health. Verlinden explains how Vincent and Wil were both “different” – different from the other siblings in their rejection of society’s prevailing norms. “They were above all willing to fight for ideals that were perhaps a little too far ahead of their time, and refused to conform to the expectations of those around them,” Verlinden writes. He goes on in appreciation, that Vincent and Wil, rather than hiding their differences, became pioneers in their own distinct ways – Vincent with his progressive art and Wil with her social causes. However, it was due to a bitter confrontation with Anna, the eldest of the Van Gogh sisters, after their father’s death, due to which Vincent was forced to leave the family home, for good. Vincent would later move to France, where he would pursue his dream of becoming a painter.

Another woman who played a crucial role in bringing Vincent’s work into limelight was his sister-in-law (younger brother Theo’s wife), Johanna Gesina Bonger, called Jo. After Vincent and Theo’s death (Theo died just six months after Vincent), Jo devoted herself to promoting her brother-in-law’s oeuvre, which led to Vincent’s first exhibition in The Hague, in 1892. A number of exhibitions then followed, and much began to be published about Vincent’s drawings and life in local newspapers. Vincent’s reputation gradually attained new heights as Emile Knappert, a friend of Wil, organized exhibitions of Vincent’s drawings in Leiden in 1904, 1909, 1910, and 1913 with the help of Jo. Jo looked after and preserved the vast body of Vincent’s letters, drawings and paintings after Vincent and Theo’s death. Verlinden states that it was Jo who became the greatest advocate of Vincent’s work, rather than his own sisters, Anna, Lies and Wil. This is clearly defended and articulated throughout the book. In 1914, Jo published Vincent’s letters to Theo, along with a short biography on Vincent’s life, Brieven aan zijn broeder (Letters to his brother). It was due to the perseverance and insight of Jo, and later her son with Theo, Vincent Willem, that Vincent van Gogh’s reputation was lifted to great heights.

Much later in her life course, Lies fulfilled her ambition to become a published writer. While her fame was initially dependent on the growing admiration for Vincent, she was later recognized “as a talent in her own right,” and was included in a selection of most important Dutch poets by the Society of Dutch Literature around 1935. From the book, we also learn about the many poetry collections published by Lies from 1907 to 1932. One of her collections called War Poems was distributed among the front line soldiers during the First World War to “support and motivate them.” She continued writing until her death in 1936; she was working on her seventh poetry collection and wrote a poem for Baarn’s local Sunday newspaper De Baarnsche Courant every month. While Lies had not been interested in Vincent for most of her adult life, she became increasingly interested in Vincent’s life and work as he rose to fame. She began to introduce herself as the sister of the famous Vincent van Gogh, gave interviews and wrote articles about her brother, and attended the unveiling of commemorative plaques in the village of Wasmes, Vincent’s workshop in Nuenen, and then at Nuenen market square, often giving lectures and speeches about her brother’s work. In 1910, Lies published her book, Vincent van Gogh: Personal memories regarding an artist, which was extended and revised later in 1923. However, Verlinden notes that Lies’ recollections were often inaccurate (she mixed up dates, occasions and locations) and the content was based on personal judgement. However, the book was a commercial success and was translated in German, English and French soon after it was released in 1910. Nevertheless, Lies achieved considerable success as a writer – she published at least six poetry collections, wrote regularly for newspapers, received considerable press attention, read her poems on the national radio, and also received funding for Support of Dutch Literature and its Writers. Although her writing did not offer her much financial support, it was definitely a feat for a woman to pursue a career in writing and get herself published during the early twentieth century.

We also learn from the book that Dorus and Anna were keen on providing their children with good education and wanted to ensure their daughter’s financial independence to prepare them for life with or without a suitable husband. Accordingly, the importance of achieving independence was impressed upon the girls from a young age. They were also given opportunities to develop their skills and broaden their prospects by their parents – Wil worked for short periods as a nurse, governess and a teacher; while Lies would go on to become a writer and publish numerous books during her later life.

This book would be a sure recommendation for all those who want to learn more about Vincent’s complex, yet emotional relationship with family as also for those who would like to know about the changing status of women during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the Netherlands. The vast and varied lives and different temperaments and dispositions of each of the Van Gogh sisters would be difficult to summarize here. Verlinden provides a detailed, descriptive (and at times, visual) account of the fascinating and varied lives of the Van Goghs, carefully unfolding the character and persona of each. The book being a poignant blend of drama, tragedy, inspiration and family love across generations, Verlinden sure paints a picture worth a curious gaze.

The Van Gogh Sisters (Verlinden, 2021), published by Thames & Hudson, is available online.