By Avani Bansal & Radhika Ghosh

Introduction: An Intriguing Conversation

I was speaking to a colleague who trains judges. Reading one of my earlier pieces on the case for representative judiciary in India, she narrated to me an incident. She said all the judges of the Supreme Court had come for training and one could see that the two female judges were more or less by their own self. So even if a woman becomes a Supreme Court judge, should we assume that she will be treated alike and at par with male judges? She didn’t think so, having observed and worked closely with judges for a long time. But she probed me deeper – “why do you think that is the case? Why do most male judges have such a parochial view towards women judges?” While I was still thinking, she said – “One of the reasons could be that the wives of most of the judges, while educated they may be, do not work professionally. So judges are still accustomed to see women in a particular light.”

Now, I had never thought about the gender gap in Judiciary in this light. While we look at the statistics of the dismal number of female judges in India at subordinate judiciary level, High Courts and Supreme Court, we rarely investigate into how the subjective worldview of our own judges with a limited role for women in it, has a deep impact on promoting, and encouraging more women to join judiciary. While many judgements in India reveal the judges’ own view on the role of women, there is no basis to assume that the same male dominated judiciary will be encouraging of more women to sit next to them as colleagues.

Let’s Look At The Numbers

The Supreme Court was established in October 1935 and functioned as India’s federal court until it assumed its present form in January 1950. The initial strength of the judges was only eight — Chief Justice and seven puisne judges. As the number of cases increased, the number of judges also went up. Today, there are a total of 31 judges, including the Chief Justice of India. Since 1950, India’s Supreme Court has had 46 Chief Justices and 167 other judges.

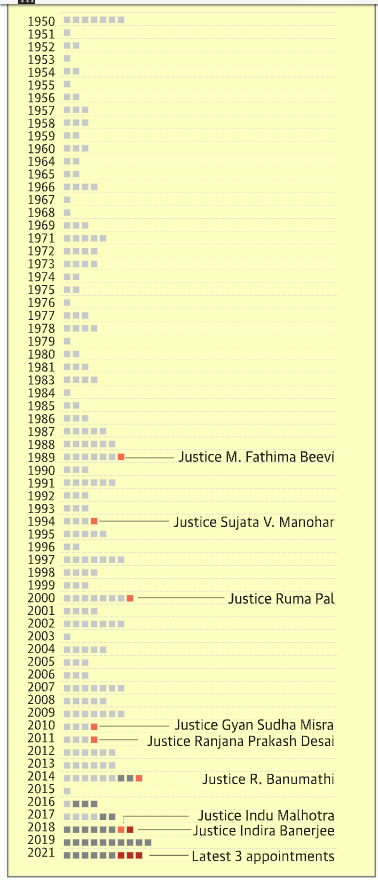

There have been a total of eleven women judges in the Apex Court ever. Three of them sworn into the Supreme Court (SC) of India on Tuesday, August 31 2021. So along with J. Indira Banerjee there are now a total of four women judges in the Supreme Court who are currently serving. This constitutes to 11% of the strength of total Judges in Supreme Court.

In 17 states, between 2007 and 2017, 36.45% of judges and magistrates were women, researchers with the Judicial Reforms Initiative at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, a think tank, wrote in January 2020 in the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW). In comparison, 11.75% women joined as district judges through direct recruitment over the same period, according to data from 13 states.

The chart shows the serving women judges (in red), retired women judges (in lighter shade of red), serving men judges/Chief Justices (in grey) and retired men judges/Chief Justices (in light red) of the SC according to their year of appointment as of August 31. Only 11 of the 256 judges (4.2%) who have served/ are serving at the apex court were/are women. Four out of the 33 judges (12%) currently serving are women.

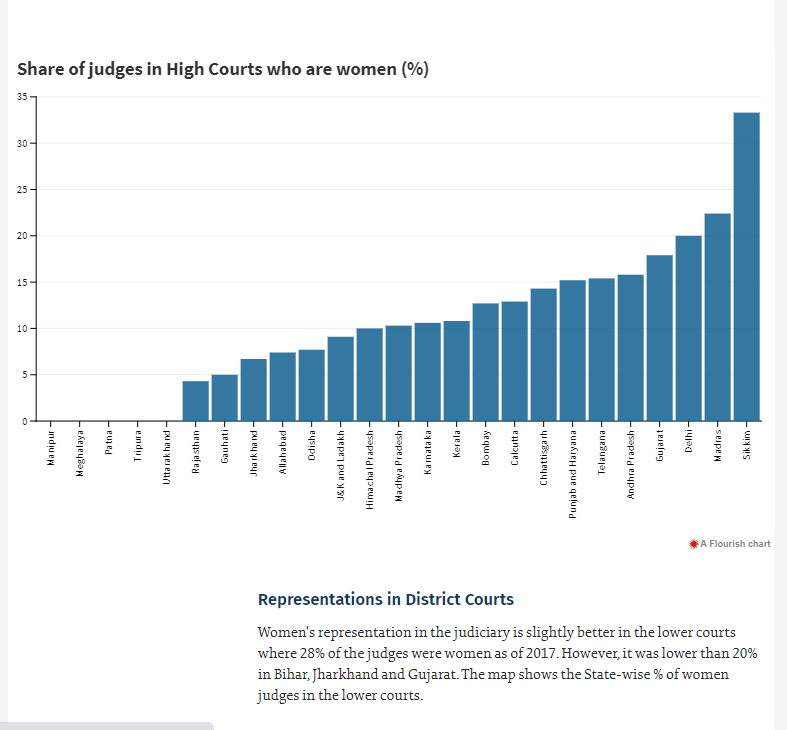

The share of women judges in High Courts was no better. The chart depicts the share of women among all HC judges as of August 1, 2021. Overall, women judges account for only 11% of HC judges. In five HCs, no woman served as a judge, while in six others, their share was less than 10%. The percentage of women judges at the Madras and Delhi High Courts was relatively high.

Women’s representation in the judiciary is slightly better in the lower courts where 28% of the judges were women as of 2017. However, it was lower than 20% in Bihar, Jharkhand and Gujarat. The map shows the State-wise % of women judges in the lower courts.

[Date available on: https://www.thehindu.com/data/only-11-women-supreme-court-judges-in-71-years-three-of-them-appointed-in-2021/article36272407.ece ]

And What About Trans Women, Dalit And Adivasi Women?

The gender gap in India is so wide that we are often talking of just ‘women’ representation without paying any attention to the inherent intersectionality debate. Women are not just one monolithic community in India. From all the eleven women who have made it as judges in the Supreme Court, there has been only one Muslim woman – J. Fathima Beewi and one practicing Christian – J. R Banumathi. There has been no dalit, or adivasi woman, and no woman representing the sexual minorities in India, including a trans woman. The intersectional representation has to be borne in mind because women representing different communities bring in perspectives which others cannot. As the International Commission of Jurists report – “Increased judicial diversity enriches and strengthens the ability of judicial reasoning to encompass and respond to varied social contexts and experiences. This can improve justice sector responses to the needs of women and marginalized groups.”

So What Explains Such A Gender Gap In Judiciary?

There are several systemic obstacles that prevent women from being equally represented in judiciary. First of all, there needs to be a clear vision of how much representation of women will be considered as adequate representation and given that women are half of the Indian population, unless there are 50 percent women judges at all levels of judiciary, we have no reason to be complacent. Having 11 percent women at HC and SC level and 36 percent women at district court level is just not good enough. We have to be convinced of raising this bar, before we start engaging in this debate.

Secondly, there is a need to revisit the rules that keep women out by appearing to treat them ‘equally’ without paying attention to the need for ‘equitable and not equal treatment.’ For example – an advocate must have a minimum of seven years of continuous practise to be eligible to be a district judge. “This could be a disqualifying criterion for many women advocates because of the intervening social responsibilities of marriage and motherhood that could be preventing them from having seven years of continuous practice,” said Diksha Sanyal, a researcher involved with the Vidhi Centre studies on this issue. While Article 233 of the Constitution provides that appointment as a district judge requires not less than seven years as an advocate, it is the Supreme Court that has interpreted it to mean ‘continuous practice’. Similarly, “the entire attitude towards women who work outside home must change,” said Justice Prabha Sridevan, a retired judge of the Madras High Court. For instance, she said that one of the reasons that reduces women to stay in power is the transfer of women magistrates every three years.

Third, we need to discuss the issue of reservation for women not just in Parliament but also in High Court and Supreme Court of India. “Reservation quota for women is perhaps just one among many factors that encourages and facilitates more women to enter the system. In states where other supporting factors are present in sufficient measure, women’s quotas perhaps help bridge the gap in gender representation,” noted the 2020 EPW special article.

Fourthly, we need to design the system in a way that incorporates the requirements of women who aspire to be judges. “A lot of female judges join the service very late, which makes their chance of making it to the high courts or Supreme Court bleak,” said Soumya Sahu, a civil judge in Madhya Pradesh. Women judges are not immune to the “leaking pipeline”, the term used to describe how many employed women quit the workforce mid-career when children face board exams and parents need additional care—jobs that fall to women. “A total reorientation of the way society thinks of family and marriage is needed,” said Justice Sridevan. “It becomes difficult if you think the woman is the sole nurturer.” To address these issues, we need to think of the challenges beyond conventional solutions that are discussed to reduce the gender gap. The gender gap in Judiciary is not separate from the gender gap that we see in all segments of society. So the need of the hour is to understand and address the requirements of women at all levels, which may require us to disrupt the current system of looking at things. Breaking the conventional ways may include more female voices at all levels of decision making and creating inclusive spaces where we don’t just engage in tokenism by appointment a few women.

Above all, what’s needed is self-reflection and being aware of our own mental barriers and perceptions regarding women and what they are capable of doing. Sometimes the attitude of judges towards female lawyers and judges may become apparent through small anecdotes that what statistics may reveal.

Justice Leila Seth, former chief justice of the Himachal Pradesh High Court and the first woman to become the chief justice of a state high court, said in a November 2014 interview with The Hindu – “In most cases, male lawyers or judges especially in upper Himachal had a feudal mentality. They were not used to a woman sitting on their head.”

Advocate Kiruba Munusamy shares an incident while in Madras High Court, where a judge commented about her short haircut, which she couldn’t tie. He said, “Your hairstyle is more attractive than your argument. Women having short hair and men having long hair, wearing studs have become a fashion these days but I don’t like it.” She replied that she has been keeping short hair since her school days. She also mentioned that she has migraine and can’t keep her hair tied for long, so she had it cut short. She then pointed out to him that there is no bar council rule or code that prescribes the hairstyle of women. His response was, “Of course, there are no rules. But I am just telling my opinion.” Kiruba was asked by other male lawyers who were present in the court room to apologise to the judge regardless of his comments. The advocate that day was insulted, mistreated and told to shut up by the judge even though she was the Petitioner’s counsel in a transwoman’s police appointment case.

While every female judge who makes it to the apex court serves as an inspiration for millions of young women, it is time that we think systematically about getting millions of girls as judges and lawyers in various courts and levels in our legal system. This will require shattering quite a few glass ceilings and setting examples through action, initiatives, policy, laws and attitudes, all of which begins with sombre reflection.

First Published here:

http://inspire.profcongress.com/inspireInside/?unique_id=perspectives_0001